It has been almost one and a half years since I started working on the prisoner's dilemma (this is not a complaint) and I still get amazed by the amount of information, insights and fun facts that I stumble upon;

- The origin of the game goes all the way back to 1950;

- Albert W. Tucker the man behind the `prisoner’s’ story was the doctoral advisor of the famous John Nash

- the prisoner’s dilemma is not being used to model only human interactions but animals as well, such as vampire bats and sticklebacks.

When I started working on the game it was already decided that I was going to follow the work of the political scientist R. Axelrod. Axelrod, as far as I know, is the first person to run a computer tournament where machines were competing against each other in a prisoner’s dilemma tournament. Axelrod’s work has received more than 30,000 citations to date and many are familiar with his work and results. You might already know that, but during the tournaments that Axelord performed the strategy that kept attracting attention was a strategy called Tit For Tat.

Tit for Tat is a much discussed strategy, submitted by Prof Anatol Rapoport in the first tournament. Tit for Tat is an example of reciprocal altruism; the strategy will always cooperate on the first round and then it will mimic the opponent's previous move.

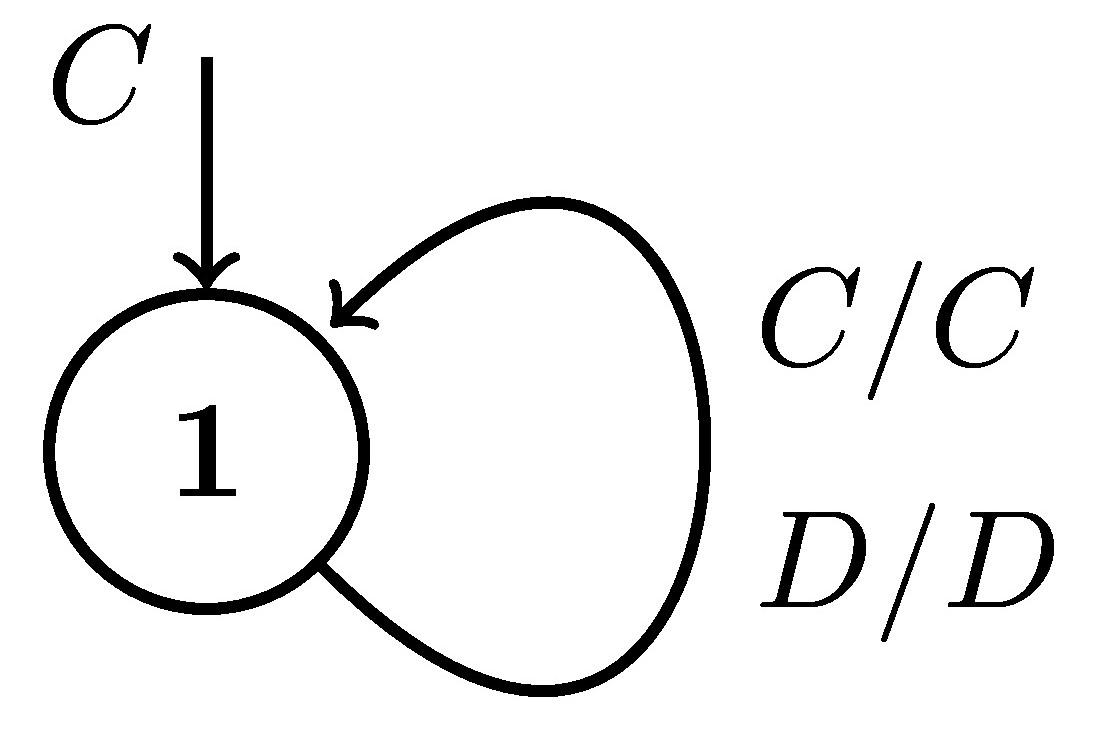

An example representation of the strategy using a finite state machine. Transition arrows are labelled O/P where O is the opponent’s last action and P is the player’s response.

The success of Tit For Tat was soon known worldwide and several researchers focused their work on the strategy ever since. But success often comes with criticism. Axelrod's tournaments assumed that each player has perfect information of the opponent's actions. In a real life situation this is not always the case. Interactions often suffer from a measure of uncertainty. This measure of uncertainty is called noise. A probability that a strategy’s action will flip.

Let’s use Axelord Python library to give an example.

>>> import axelrod as axl

>>> players = [axl.Defector(), axl.Cooperator()]

>>> match = axl.Match(players=players, turns=10)

>>> match.play()

[(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C)]

>>> axl.seed(1)

>>> match = axl.Match(players=players, turns=10, noise=0.1)

>>> match.play()

[(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(C, D),

(D, C),

(D, D),

(D, C),

(D, C),

(D, D)]Defector and Cooperator are deterministic strategies. Thus, their actions are always known. In the example above, we can see that for each of the ten turns, Defector will always defect and on the other hand Cooperator always cooperates. This now changes once noise is introduced. The 5th, 7th and 10th actions of Cooperator have now flipped to be defections.

When this stochasticity was introduced in the tournament environment the performance of Tit for Tat was proven to suffer, especially against itself.

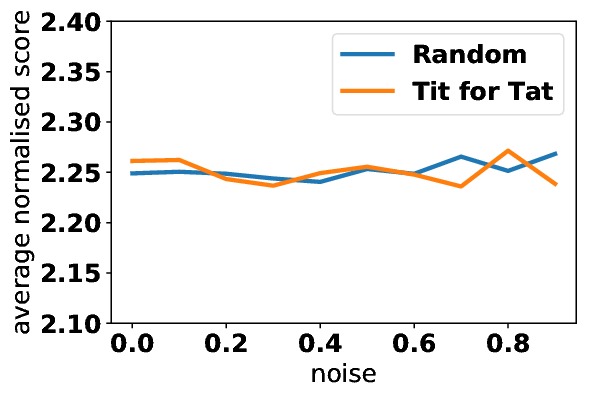

Reading about the strategy I came across an article written in 1985 by P. Molander, The Optimal Level of Generosity in a Selfish, Uncertain Environment, who spoke about a dark side of the strategy. Using Markovian modelling, Molander claimed that if two strategies playing Tit for Tat meet in a noisy match the average payoff that a strategy will receive will be the same as that of a Random player (with probability 0.5 of cooperating).

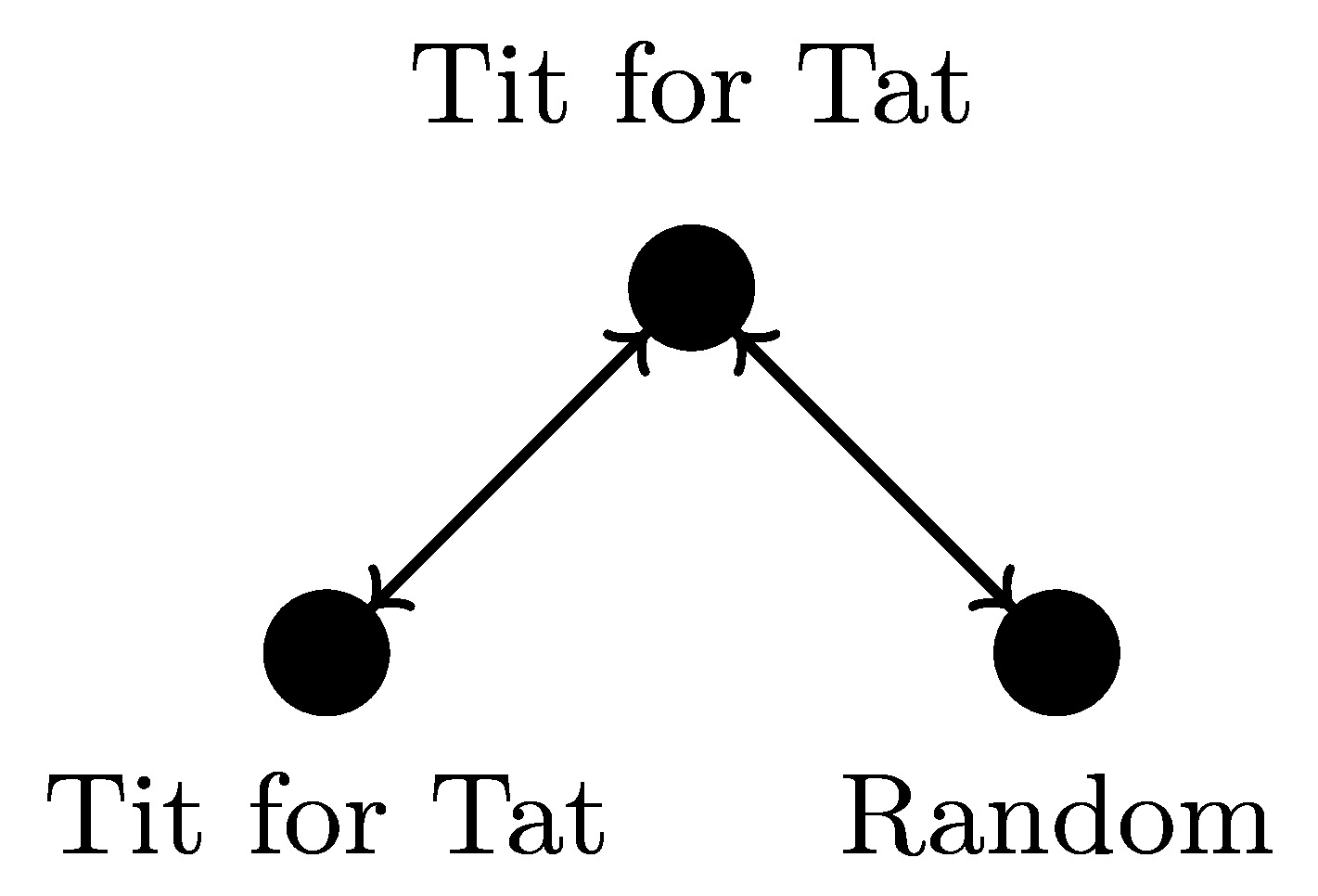

Once again using the Axelrod library we can create the two matches and test the hypothesis. More specifically, two matches for different values of noise, ranging between 0 and 1 are performed. The first matches are between two Tit for Tat strategies and the second between a Tit for Tat and a Random(p=0.5) player, as illustrated in the picture below.

To create the matches we use the following code:

>>> noise_v = 0.1

>>> match_one = axl.Match([axl.TitForTat(), axl.TitForTat()],

... noise=noise_v, turns=500)

>>> result_one = match_one.play()

>>> match_two = axl.Match([axl.TitForTat(), axl.Random()],

... noise=noise_v, turns=500)

>>> result_two = match_two.play()After performing a number of these, the average score of the strategies for each match is kept on record. By plotting the average scores, we can test the hypothesis which is proven to hold.

The strategy Tit for Tat and the importance of reciprocal behaviour have been milestones in the field of the iterated prisoner’s dilemma. The results of Axelrod’s initial tournaments have received criticism and a good argument is that maybe the strategy was positively affected by its environment! Including the list of opponents and the fact that noise was not taken into account. The theoretical claim of Molander and the empirical proof show that the highly praised strategy Tit for Tat has disadvantages and that it suffers a lot from them. For in a noisy environment the strategy is not any better than a Random player!

To close off, I would like to highlight the usefulness of well written research software! The Axelrod project allowed me to easily reproduce a work which dates back to 1985 and give an empirical prove to a fascinating fact!